Intro to Cybersecurity

Categories: Cybersecurity

Tags: Cybersecurity

This article explains the general idea of cybersecurity. It is a collection of notes I have gathered online and is freely available to read. I recommend reading through my OSI layer 1-2 and 3-4 articles to get a better grasp of networking terminology.

Terminology:

- Cybersecurity: The study of information security policy. It presents a way to protect people from harmful attacks online.

- Authorization: The process of verifying what a person has access to.

- Authentication: The process of verifying the person's identity.

- Cyberspace: An environment where anything digital takes place. It is a word that serves as a contrast to "in real life". We use "internet" to represent ourselves in "cyberspace".

- Internet: A service provided by Internet Service Providers (ISPs) that involve the use of TCP/IP protocol suite. We use "internet" to stay online in the "cyberspace".

- Vulnerability: A system flaw that could be exploited to compromise the system.

- Zero-day Vulnerability: A flaw in a system not known to software developers but known to attackers (i.e. STUXNET and Log4Shell).

- Exploit: The software in the system used to take advantage of a security bug or vulnerability.

- Malware: "Bad" software running on a computer for malicious purposes. Examples include viruses, trojans, ransomware, worms, rootkits etc.

- Access Point: A hardware networking device that allows Wi-Fi devices to connect to a wired or wireless network (in a home setting, it is already built into an ISP modem).

- Default Gateway: A portal of Local Area Network (LAN) to let internet traffic arrive.

Introduction

CIA Triad

In the world of cybersecurity, it is important to contain information within reasonable limits on the internet.

There are three ways to ensure this:

- Confidentiality: Only a specific group or person is authorized for data access (i.e. using password or biometrics)

- Integrity: Keeping data accurate and not compromised or tampered with. It must remain trustworthy and unchanged unless modified by authorized users.

- Availability: Data is readily accessible for public or private use.

Together, they form what is called the "CIA Triad". It is the guiding model for designing information security policies.

Cybersecurity Frameworks

As computer security needs were becoming more demanding in the early days of computing, it became necessary to report and share incident findings via a standard framework.

One of the most popular one is a study made by Lockheed Martin Corporation to find definite patterns of malware penetrating inside a computer or system. They have formulated a model and The Cyber Kill Chain was created for referential use.

Cyber Kill Chain (CKC) is a strategic framework that provides a systematic understanding and mitigating cyber threats:

Note: This model is not the only way to track down the stages of a cyberattack. It is only there as a reference and assumes the attacks are linear (they often loop, skip, or overlap stages)

- Reconnaissance: Find/recognize the target ("casing the joint")

- Weaponization: Create a malicious payload (code) exploiting a known vulnerability.

- Delivery: Transmit the weapon to the target (e.g., email attachment, malicious link, USB drive).

- Exploitation: Trigger the malicious code to take advantage of the vulnerability.

- Installation: Install malware or a backdoor on the compromised system.

- Command and Control: Establish communication between the compromised system and the attacker.

- Action on Objectives: Carry out the attacker’s goals (data theft, sabotage, etc.).

This is just one of the many frameworks. Other popular frameworks include:

We are not going to focus on these frameworks in detail as they are beyond the scope for an introductory cybersecurity article. It's good however to be aware of their existence.

The Three Types of Software

When users start interacting with computers and the internet, they may notice three different types of software: goodware, grayware, and malware.

| Type | Characteristics | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Goodware | Obtained from trustworthy source | Official OS updates or vendor-signed programs |

| Grayware | Software that is not outright malicious but may have unwanted features | Potentially unwated programs (PUAs), bloatware, adware, spyware |

| Malware | Software that is made to cause harm to its recipient | Virus, Trojan, Worm |

Note: You may find "spyware", "adware", and "trackware" in the "grayware" category. Depending on the true intent of the hacker or developer, both "adware" and "spyware" are often malicious by nature. Therefore, it's better to consider them as "malware" instead

Hats

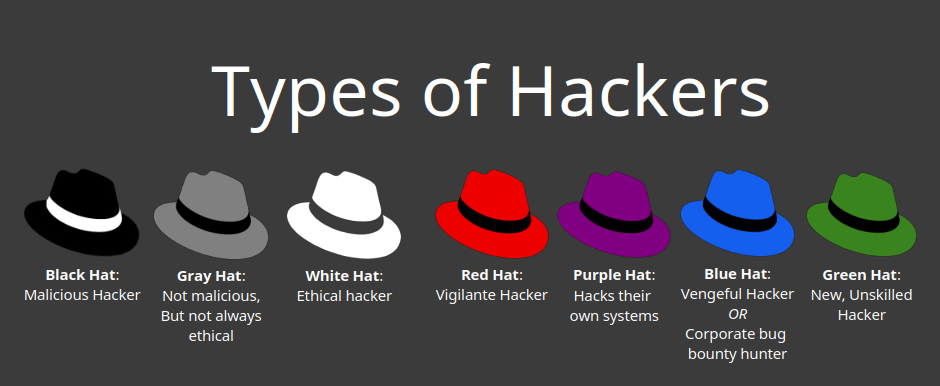

The word "hacker" is often misunderstood. Although it colloquially implies a bad-actor in the cyberspace, it is more nuanced.

As we see in this picture, every type of hacker has different responsibilities. The colours for ethics are "white", "gray", and "black":

- Black: Hackers that commit illegal acts ("the bad guy"). e.g. steal personal information/money, destroy IT infrastructure, commit fraud etc.

- Gray: Hackers that commit illegal acts but without malicious intent. e.g. exploit security flaws without permission, but report them afterward.

- White: Hackers that commit legal and ethical acts ("the good guy"). e.g. They are altruistic and care about people's privacy and dignity.

Specialized hackers include:

- Red: Hackers that specialize in offensive security.

- They're often perceived as people who simulate or commit aggressive attacks for ideological purposes. They also prevent and punish crimes without a police warrant. (Hence, "vigilantes").

- Groups infamous for red hat hacking include Anonymous, SiegedSec, and others.

- Blue:

- Hackers that specialize in defensive security.

- They are recruited by companies to defend IT infrastructure with the sole purpose of protecting, patching, monitoring etc.

- OR... Hackers that seek vengeance for retribution.

- They are disgruntled people that believe their target is in the wrong. The do not do it for money, they do it out of spite to enact personal retribution or social justice.

- Hackers that specialize in defensive security.

- Purple: Hackers that self-teach and experiment their IT infrastructure.

- They like to combine the best of blue and red hat hacking techniques to push the limits of IT security.

- Green: Hackers that are relatively new to the field of cybersecurity. They are committed to learn and improve their IT skills.

- Script Kiddies: Hackers that do not like to learn. They just want to find shortcuts to commit malicious acts.

Attack Indicators

Computer hackers make the world either a safe or dangerous place. Among the least ethical hackers, they create software known as "malware".

Malware: A type of program made by bad actors designed to cause harm or exploit computer systems or devices. It is a portmanteau of "malicious software".

In order for attackers to achieve successful objectives, it will always require "social engineering".

Social Engineering: It is the use of psychological influence on people into performing actions with bad intent. Examples include a fake look-alike of a banking website, a corporate email, adware, etc. Lying, eavesdropping, deceiving, and tailgating (following someone closely) are all considered both online and offline.

Malware is categorized by their penetration (infection) and payload (behaviour). They can do one or multiple things and can overwrite system files, damage booting processes, encrypt sensitive files, steal personal information, etc.

Hackers usually incorporate malware with some or all of the characteristics above based on the following multiple categories in their malicious code.

Important: Cybersecurity textbooks or articles like to describe how there are different "types" of malware. The thing is, a certain malicious program can be a virus (by penetration), a trojan (by payload), and a spyware (by payload) all in one. It is very common to find overlapping features based on how malwares penetrate systems, how they hide, and how they behave. It is better to think of the following list as labels or functions rather than mutually exclusive "types".

The three main categories are:

- Virus: Malware that replicates itself by infecting an executable file.

- It almost always attaches itself to an executable file.

- It requires the user or a host program to trigger it.

- Worms: Malware that can self-replicate on its own.

- Like viruses, it also spreads itself to other computers.

- Unlike a virus, it does not involve user interaction at all.

- Trojans (a.k.a Trojan Horse): Malware that misleads users its true intent.

- A stand-alone malware disguised as a legitimate software and acts as a cover for hidden actions.

- Unlike viruses and worms, they do not self-replicate.

This table gives a clearer picture:

| Parameter | Virus | Worms | Trojans |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main target | Attacks the files in the system | Attacks the systems in a network | Attacks the users in a system |

| Replication | Yes | Yes | No |

| User Interaction | Yes | No | Yes |

| Reproducibility | Reproduce by infecting other files | Reproduce by itself | None |

| Impact/Payload | File corruption, system instability | Network slowdown, system crash, delivery of other malware (Trojan) | Stealing data, providing Remote Access Trojan (RAT), or delivering ransomware |

A few more examples include:

- Spyware: Malware that strictly spies people. It includes keylogging, unauthorized camera/microphone access, logging activities, location tracking etc.

- Rootkit: Malware specifically designed to corrupt operating system functionality.

- RAT (Remote-access Trojan): A more sophisticated trojan that enables attackers to establish a covert/hidden communication channel (backdoor) for complete unauthorized computer access.

- Adware: Malware/Grayware that presents unwanted ads. It can be in the form of too many irritant pop-up windows.

- Ransomware: Malware that encrypts user data and extracts ransom from the user. If the ransom is not met, the computer becomes compromised.

Other programs involving malware include:

- Keylogger: Logs all the keysstrokes users enter with their keyboards.

- Bot: A software application that automatically performs one or multiple tasks. Bots that are distributed on the network form a botnet (portmanteau of "bot" and "net").

- Logic bomb: A set of instructions in a program that carries malware (i.e. malware or worm) only after certain conditions are met.

Attack Techniques

Beyond malware infections, hackers achieve the same objective by delivering techniques to exploit vulnerable networking protocols or deceive users.

Networking Attacks

In this section, we'll showcase three major attack types based on the CIA Triad (Confidentiality, Integrity, and Availability).

| Attack Type | Target: Confidentiality | Target: Integrity | Target: Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| DDoS | Low | Low | High |

| MitM | High | Medium-->High (if active), Low (if passive) | Low |

| SQL Injection | High | High | Medium |

Note:

- MitM has an interesting place for Integrity. Depending on the attack, it can either be passive or active. If passive, hackers only read data. If active, hackers can read AND potentially modify packet flow, corrupting networking/system integrity in the process.

- It is important to highlight that such attacks are deeply woven together. By combining various techniques, a single attack can practically violate all three pillars that compromise confidentiality, alter integrity, and disrupt availability.

We'll start with DoS:

DoS and DDoS Attack

DoS (Denial-of-service) or DDoS (distributed denial-of-service) are attacks that both seek to make machine(s) or network unavailable to its intended users.

The core difference between DoS and DDoS is the number of systems attacking.

A DoS (Denial of Service) attack comes from one computer.

A DDoS (Distributed Denial of Service) attack uses many computers to flood the target. The attacker breaks into multiple computers ("agents") and installs secret programs (malware). This setup allows the attacker to become the "master" of a large fleet. With just a few simple commands, they can instantly order all the compromised computers to launch a much bigger and wider attack.

Here is an image to illustrate:

Man in the Middle (MITM) Attacks

A Man (or Meddler) in the Middle (MitM) (a.k.a On-Path Attack) is a cyberattack that involves the attacker secretly intercepting and relaying communication between two directly connected hosts. The attacker can monitor, capture and modify data exchanged between the two hosts.

Its primary objective is to violate confidentiality (eavesdropping, steal credentials etc.). If the attack is not passive, they can modify information flowing through the network.

MitM can involve the following methods:

Note: The words "spoofing" and "poisoning" might be colloquially used interchangeably. It is more precise to see "spoofing" as the action " and "poisoning" as the result.

- Rogue Access Points: Attackers create passwordless Wi-Fi access points with names similar to legitimate ones. If victims unwillingly connect to these, all their online traffic will pass through the attackers' device.

- ARP poisoning (ARP Spoofing): Attackers broadcast over the local network the mapping between the IP address of a legitimate device and the MAC address of their own device. This is possible only when the perpetrators have access to the victim's local network.

- DNS Cache poisoning (DNS Spoofing): Occurs by changing or corrupting entries in a DNS cache (e.g. any device with a DNS cache like on a router, a personal computer, or a DNS server). The end result is the user being directed to a malicious copy of a website that is indistinguishable from the original.

- IP Poisoning (IP Spoofing): Occurs when an attacker disguises themselves as a legitimate user by having their IP packets bypass IP authentication.

We will go through each one:

Rogue Access Points

A Rogue Access Point is a wireless access point (AP) installed on a secure network without the knowledge of the system administrator (unless if it's deliberately there for testing reasons). It may be a standalone hardware device like an AP connected to a switch, a router or any networking device. It can also be a software-based AP ("evil twin") that imitates a legitimate AP.

If ignored, the consequences are:

- It provides a wireless backdoor into the network for outsiders.

- It bypasses the network firewalls and other security devices.

It can involve:

- Direct Rogue AP connection: The attacker plugs a customized hardware (Access Point) into a network to provide a persistent wireless backdoor bypassing all security controls and access to internal resources.

- Example: It's like someone entering a bank through a side door that isn't supposed to open. Instead of having networking traffic flowing in the right route, they are misaligned but then reverts back to its destination (an effective MitM attack).

- Evil Twin: It is a type of rogue AP. Its purpose is to imitate an access point by jamming any legitimate wireless signals or use repeaters in order to effectively trick users into connecting the attacker's network instead of the real one.

- Example: If a person with a laptop at Starbucks would like to connect to public internet, they may be prone to seeing a legitimate SSID (AP's name like "Starbucks Wi-Fi") but unknowningly thinks that it is fake.

ARP Poisoning

It is a layer 2 layer attack that tampers with MAC addressing.

If the attacker has access to the local area network, they can broadcast ARP messages to associate the attacker's MAC address with the IP address of the default gateway (or any routing devices). This allows the attacker to intercept and control all local network traffic between users and the internet.

As shown in the picture above, instead of traffic flowing through hub/switch's ARP cache, it is flowing through the attacker's ARP cache. This can give the attacker control of all Layer 2 operations.

- Identify the target: The attacker identifies the IP and MAC addresses of the target host (victim) and the Default Gateway (router).

- Poison the target: The attacker sends forged ARP replies to the target host, falsely claiming the attacker's MAC belongs to the Gateway's IP.

- Poison the gateway: The attacker sends forged ARP replies to the default gateway, falsely claiming the attacker's MAC belongs to the target host's IP.

- Traffic interception: With both ARP caches updated, the attacker is now the Man-in-the-Middle (MiTM). All traffic flows through the attacker's machine.

- Eavesdropping and forwarding: The attacker captures and analyzes the intercepted packets (e.g. using Wireshark) and then forwards the traffic to the legitimate destination to keep the connection alive.

DNS Cache Poisoning

Note: It goes by various names: "DNS hijacking", "DNS (cache) poisoning", or "DNS redirection".

DNS cache poisoning is a cyberattack that tricks the computer into accepting a fake DNS record. It works by modifying the name resolution of a genuine URL to point the user into a compromised DNS server. If this happens in a business setting, it can affect multiple networks at a large scale.

So, if the user tries to access a legitimate site, it will redirect to a fake version of the said site (the user still sees google.com even when hovering on it, but it still redirects to the fake version due to DNS name resolution). The attacker can then attempt to steal personal information (spyware) and can also infect the computer via user installation with a trojan or a virus.

- Inject DNS Cache: Attacker injects fake DNS entry. This will make the target's IP address be associated to the IP address of the attacker's fake server.

- Initiate legitimate request: User issues a request (HTTP GET) to a legitimate website by typing the URL. This will require DNS lookup which has already been compromised.

- Request resolution redirection: Request resolves to a fake website.

- Malicious Payload Delivery: "Spoof" the user and compromise their computer with social engineering.

IP Poisoning

IP spoofing is the creation of internet protocol (IP) packets with a false source IP address. Its main purpose is to impersonate a different user in the network.

If we use the above image as an example:

The attacker (1.1.1.1) wants to flood a victim (3.3.3.3) while hiding.

-

The Attacker's Deception: The attacker (1.1.1.1) sends a packet to the server (2.2.2.2). The attacker falsifies the source IP address in that packet, setting it to the victim's address (3.3.3.3).

-

The Server's Reaction: The server (2.2.2.2) believes the request actually came from 3.3.3.3.

-

Traffic Misdirection: When the server (2.2.2.2) sends its reply or answer, it sends it back to the address it saw in the source field: 3.3.3.3.

-

The Victim is Flooded: If the attacker does this repeatedly, using many servers like 2.2.2.2, all of those servers' replies are directed to the single, innocent victim at 3.3.3.3. This will cause a flood and the trusted host becomes the target of a DDoS attack.

Social Engineering (SE) Attacks

Phishing is deception designed to impersonate or trick users into submitting data for malicious use (harvest info or spread malware).

The most of famous of SE Attacks is phishing, it comes with many forms:

URL Spoofing

URL spoofing is an attack that requires heavy social engineering. It is the redirection of a genuine site to a fraudulent look-alike designed to steal sensitive data or install malware. It can be considered MITM only if the attacker acts as the intermediary between the user and the legitimate server.

It is similar to DNS poisoning, but it does not involve any DNS cache change. A hacker will only create a fraudulent website and a deceptive link which serves the same purpose as DNS spoofing.

It can come in many ways:

- Misleading Unicode characters (Homograph attacks): Attackers register domain names with characters from other alphabets that look almost identical to ASCII cahracters (Cyrillic "а" vs. Latin "a") or use puny-encoded domains (xn--...) to visually display like a trusted domain.

- Very long URLs (URL Padding/obfuscation) Long URLs include the legitimate brand early in the string but bury the rest (e.g. https://www.google.com.attacker.com/). This is especially common for devices with small screens that truncate the full URL to appear legitimate even though it belongs to the attacker.

- Typosquatting: Users who mistype a URL (goggle.com instead of google.com) may land on these pages and be prompted to enter credentials or download malware.

Cryptology

If the buns of a burger are the infrastructure, the patty is the cryptology.

There is a lot to unpack, here are concise definitions of all relevant topics to cover:

Cryptology: It is the study of secure communication (codes).

Cryptography: A subset of Cryptology. It is the study of creating and encrypting data.

Cryptanalysis: Another subset of cryptology. It is the study of deciphering and decoding encrypted data (without being told the key).

Steganography: Similar to cryptography, but it does not encode information. It hides it instead.

Now with that out of the way, we'll start talking about cryptography.

Cryptography

Cryptography requires encryption. With encryption, there are many ways to conceal text from adversaries. From Caesar ciphers to Zodiac letters, and from Enigma machines to Quantum encryption, they all have one thing in common: ciphers.

Note: It is important for readers to emphasize the difference between "encoding" and "encrypting". They may sound like they're mutually intelligble, but there are nuanced differences.

Encrypting: The process to conceal data that can be deciphered later on. It requires an algorithm and a key. Examples include AES, RSA, and Blowfish

Ciphertext = Algorithm(Plaintext, Key)

Encoding: Unlike "encryption", the key is out of the picture. It is only used to map or transform data such that other programs can use (pictures, videos, audio etc.). In ths equation below, "Mapping System" can be ASCII, Unicode, Base64, and HTML URL encoding.

Encoded Data = Transform(Data, Mapping System)

The confusion lies on the fact that encoding and encrypting is done at the same time. The thing is, we encrypt data first (if there's a key to use), then we encode it allow sharing to other devices. You cannot encode by encrypting.

There are four things to take note here. We have ciphertext, plaintext, key, and cipher. Here is a basic illustration:

Out of these four, the are two main ones:

- Cipher (or cypher): The algorithm to encrypt data. Its objective is to turn plaintext into ciphertext.

- Key: It is used alongside the cipher. This makes data accessible only to those who obtain it.

Here's an analogy:

Cipher = lock design

Key = the actual key that opens that specific lock.

General applications that require ciphers include browsing, cloud storage, and VPNs, SSH vs. telnet, application-level internet connectivity like HTTP vs. HTTPS (via TLS) etc.

Historically, ciphers were simple to use and easy to break. It heavily relied on word analysis and linguistic patterns. But over time, it became harder to crack with advanced mathematical methods and heavy use of number theory, probability, statistics etc.

It depends on the choice of cipher and the key tied it to perform a desired operation. In order to decide on what cipher to use, we can rely on two properties to determine their security strength: confusion and diffusion.

| Property | Description | Goal | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Confusion | - Makes the relationship between the encryption key and the ciphertext as complex as possible. - A single change in encryption key bit will affect many ciphertext bits. | Prevents attackers from deducing the key from the ciphertext. | Substitution: Replace a letter or block of substrings with a corresponding letter or substring. |

| Diffusion | - Makes the relationship between the plaintext and the ciphertext as complex as possible. - A single change in plaintext bit will affect many ciphertext bits. | Prevents attackers spotting plaintext patterns. | Transposition (Permutation): Reorganize or rearrange letters based on a specific pattern or algorithm. |

At the end of the day, if data systems are not properly encrypted or do not meet the admin's objectives beforehand, they become vulnerable from outside attacks. Because of this, strong oversight and adaptability will be required for multiple cryptographic algorithms for different applications. They will rely on a suite of algorithms working together called "cryptosystem".

Cryptosystem: A suite of algorithms for key generation, encryption and decyption operations.

Several principles influence the design of cryptosystems, with one of the most recognized being Kerckhoffs’s Principle (summarized by Claude Shannon's maxim's "the enemy knows the system"). This principle asserts that a cryptographic system should remain secure even when its design and algorithms are fully known to adversaries as long as the keys remain confidential.

Based on the CIA Triad, there are three key points for cryptography (we'll get into all these in the Cryptographic Building Blocks chapter):

- Confidentiality of data: Encryption algorithms like AES, ChaCha20, or RSA (for key exchange)

- Integrity of information being sent and received: Via hashing (SHA-256, SHA-3) and HMAC (HMAC-SHA256, HMAC-SHA1)

- Authentication (or non-repudiation): Via digital signatures such as RSA-PSS, ECDSA, or EdDSA (Ed25519)

From here on, I will bring the topic about "encryption". There are two main types of key-based encryptions:

- Symmetric Cryptography

- Asymmetric Cryptography

Each of these has its ups and downs, but both are widely used.

Symmetric Cryptography

When both parties use the same key to encrypt and decrypt messages, it is referred to as symmetric encryption.

In this image, we can see both sides' use the same key to encrypt and decrypt (hence, "symmetric"). The process is very simple:

- When Alice sends a message to Bob, Alice will encrypt the message using the secret key.

- When Bob receives Alice's message, Bob will use the same key Alice uses to decrypt the message.

- It's the same vice versa.

It is pretty intuitive right? But here's the thing, how did both Bob and Alice end up using the same key? Surely they did not send the key and the message together as packets? This is obviously far from what's happening as it can be prone to attackers eavesdroping and performing MitM attacks.

Both peers exchange keys asymmetrically. Here's a long digest:

- Set up public parameters Before any messages are sent, the "rules of the game" must be established. In TLS 1.3, these are defined by the Named Group (e.g., ffdhe2048) found in the RFC 7919. Both sides agree on:

- $g$ (the Generator): A small base number (usually 2).

- $n$ (the Modulus): A very large, mathematically "safe" prime number.

Note: If all this is confusing or overwhelming to you, I recommend reading or skimming through all these references here, here, here, here (extremely comprehensive), and here.

-

Agree on the key: Both computers will have to agree on a secret (public) key that is derived from both $g$ and $n$. This is done with Diffie-Helman (DH) or RSA key exchange under TLS. For DH, it is an asymmetric process where each peer has to have its own private key in order for both peers to transition to symmetric encryption:

-

Generate the key: Both the client and the server will generate its own private key and will never be made public. It is done with the use of good pseudorandom number generators (it depends on how the program is coded. It will use either OS and programming language features, e.g.

/dev/randomin Linux oros.urandom()in Python). If the the key derives from a password (like signing in an account), a Key Derivation Function (KDF) is used (the most popular ones are PBKDF2HMAC or HKDF) -

The Client (ClientHello): The client is now gonna inform the server on what will need to be done: "Hey! I want to speak TLS 1.3. Here is a list of cipher suites I support. My highest preference comes first. E.g.:

-

00 08 13 02 13 03 13 01 00 ff

00 08 - 8 bytes of cipher suite data

13 02 - assigned value forTLS_AES_256_GCM_SHA384

13 03 - assigned value forTLS_CHACHA20_POLY1305_SHA256

13 01 - assigned value forTLS_AES_128_GCM_SHA256

00 ff - assigned value forTLS_EMPTY_RENEGOTIATION_INFO_SCSV

Also, I presume you know how to do Diffie-Hellman for exchanging keys, so I've attached my Key Share (my public math part $A$) to this message to save us some time. I got $A$ by combining both the gernator $g$ and the my private key $p_c$ which I've already generated on my own. You will only need $A$ and I will leave you at that". The client will never reveal $p_c$ to the public.

$$\text{Key Share } (A) = g^{p_c} \pmod n$$

- The Server (ServerHello & EncryptedExtensions): "No problem! I agree to use TLS 1.3 and the

TLS_AES_256_GCM_SHA384suite. I already just got my own private random number ($p_s$) and I also accept your 'Key Share' guess $A$. Here is my Key Share (my public math part $B$) in return.

$$\text{Key Share } (B) = g^{p_s} \pmod n$$

By the way, here is my Digital Certificate (to prove I’m really who I say I am) and a Digital Signature to verify that all this math we just did hasn't been tampered with."

Now, the Client calculates $K = B^{p_c} \pmod n$ and the Server calculates $K = A^{p_s} \pmod n$. Both results land on the exact same number. This number will now be used to do symmetric encryption.

Note: I have used the regular DH method instead of Ecliptic-curve Diffie-Hellman (ECDH) because discrete logarithms are better understood for people with no background in Ecliptic-curve cryptography (ECC). It is an advanced topic that requires a heavy dose of math knowledge. If you're still interested, I recommend watching a high-level explanation here.

If you would like a simplified video demo, this is an excllent one made by Spanning Tree:

-

Start encrypting the data and send it: Now that we have the shared secret key, the software can now start encrypting and converting plaintext into ciphertext by using an encryption algorithm like AES (Advanced Encryption Standard) or DES (Data Encryption Standard). As of writing this article, AES-256 is the standard (this will require the secret key to be 256 bits long).

-

Decryption: At this point, both the host and the receiver are prepared to decrypt ciphertext to their corresponding decryption algorithm.

Notes:

- Both DES and 3DES (Triple DES) are obsolete (NIST made the announcement to stop the usage by 2017). I mentioned both "DES" as 3DES' as AES was not the only one.

- TLS is the successor of SSL (TLS 1.0 was actually SSL 3.1). The reason why both SSL and TLS are conjoined together as "SSL/TLS" is because SSL was made at a time when Netscape browsers were the norm. As soon as Microsoft Explorer overtook the web browsing market, Microsoft and Netscape made a deal to have SSL be taken over by IETF. It was also agreed to have the name changed to TLS upon Microsoft's request. Even then, a lot of people did not adapt and still referred to it as "SSL" and not "TLS" (old habits don't die). To make up for this confusion, you may find websites that call it "SSL/TLS" instead (nodding the legacy of LTS).

- RSA is both a key-exchange mechanism and a encryption mechanism.

Asymmetric (Public-Key) Cryptography

In Asymmetric encryption (a.k.a "public-key cryptography"), different keys are used.

When both parties use different keys to encrypt and decrypt messages, it is referred to as asymmetric encryption. Each party has a pair of a public key and a private key.

In these pictures, we are seeing Bob is sending a secure message to Alice and vice versa.

- If Bob wants to send a message to Alice:

- Bob needs his private key for signing (if used) and Alice's public key for encryption. Alice needs her private key for decryption and Bob's public key for verification (if used). Both need to know the other party's public key.

- If Alice wants to send a message to Bob:

- Alice needs his private key for signing (if used) and Bob's public key for encryption. Bob needs his private key for decryption and Alice's public key for verification (if used). Both need to know the other party's public key.

- Public keys: They are used to encrypt plaintext and verify digital signature. They can be freely distributed or shared.

- Private keys: They are used to decrypt ciphertext and create digital signatures. To ensure security, they must not be shared.

Two important points for private keys:

- If the wrong private key is used, the ciphertext cannot be decrypted.

- If the private key is sent to anyone, anyone can impersonate the owner of the said key.

Although it is not fast like in symmetric cryptography, it eliminates the need for a secure key exchange between two parties and provides better use of confidentiality and integrity. This is effectively done through the use of digital signatures and encryption schemes that ensure messages remain confidential while preventing any unauthorized modification (e.g. The browser sees Certificate Authorities (CAs) to ensure authenticity).

I have found two excellent video lectures made by Ross Bagurdes and Practical Networking. They both perfectly describe how the key exchange works to start up symmetric and asymmetric encryption. I can't recommend these enough:

Cryptanalysis

Cryptanalysis is the opposite of cryptography. It looks for hidden messages and decipher/decrypt them even if the key is not known.

Cryptanalysts' main goal is to discover vulnerabilities or flaws that can expoit the system's security.

It is common for attackers to use cryptanalytic methods in order to decrypt data and break the system's security. It is very much akin to solving a puzzle to gain access, exploit, and crack software/hardware vulnerabilities or protections.

They are done through various ways:

- Ciphertext-Only Analysis (COA): The attacker has access only to encrypted messages (no algorithm info and no partial plaintext). It becomes extremely challenging to crack.

- Known-plaintext analysis (KPA): The attacker needs to have access to some or all of the plaintext-ciphertext pairs in order to determine the key used to encrypt the message.

- Chosen-Plaintext Analysis (CPA): If the attacker knows the encryption algorithm or has access to the device used for encryption, they can figure out the key by sending a batch of random/similar plaintexts at once to get corresponding ciphertexts. The attacker will try to deduce and compare that against the ciphertexts they are trying to crack.

- Adaptive Chosen-Plaintext Attack (ACPA): Similar but unlike the CPA, the attacker has the advantage of finding and narrowing down the key after every chosen plaintext. For every ciphertext received, they can narrow down further to recover the key (note that this can happen if the cryptosystem implemented is not well secured).

- Man-in-the-Middle Attack (MITM): As mentioned in this sub-chapter, the key can be retrieved if the meddler performs unauthorized key exchanges with two hosts. This way, login credentials can be obtained to access sensitive data (i.e. can be done with Wireshark or the like).

For summary, here is a table for tldr (link):

| Type of Attack | Cryptanalyst Task |

|---|---|

| Ciphertext Only (COA) | - The attacker has access only to the ciphertext. - They try finding the key with no additional information. |

| Known-Plaintext (KPA) | - The attacker knows the ciphertext IN ADDITION to some pieces of the plaintext. - They find the encryption key thanks to some information. |

| Chosen Plaintext (CPA) | - The attacker CHOOSES the plaintext to encrypt to access its correspoding ciphertext. - Evaluate encryption key with chosen plaintext inputs. |

| Adaptive Chosen Plaintext (ACPA) | - Evaluate encryption key with advanced CPA method(s). - Chose subsequent plaintexts based on the information gained from received ciphertexts to figure out the key. |

| Meddler-in-the-Middle (MITM) | Manipulate encryption of a communication channel between multiple hosts. |

Examples of real life cryptanalysis:

-

For KPA:

Enigma Weather Reports: Both Polish and British mathematicians have managed to crack Germany's Engima Machine. It becmae KPA as even before WWII, the British obtained ilues by the Polish Cipher Bureau. This forced both the Germans and the Allies to adapt on their intelligence work.

The British every 6 AM were well-aware of the weather reports by Germans. The weather reports are not very dynamic and do not require much analysis thanks to previous knowledge gained early on. This can be essential to infer or deduce other ciphertexts.

PS3's ECDSA Failure: Fail0verflow found that the PS3's ECDSA algorithm verified every signature with the same random key number. By having this number as an accidental constant, you can run unsigned firmware on the console (read here for more info).

-

For COA:

RSA key cracking: In the early 2000s, RSA was found to have an exploit by factoring large prime numbers. To remedy this, the key lengths became longer to make them more resistant to attacks.

Zodiac 340 crack: Z340 took 51 years to decipher. Initially, there were various clues, But it took computing power and non-intuitive pattern finding methods to decrypt it.

-

For CPA:

Bletckley Park "Gardening": During WWII, the British sent predictable messages through a tactic called "gardening". Gardening is a method to force the target send a reactive encrypted message.

With "gardening", they gathered "cribs" (predictable pieces of plaintext) by laying mines at specific coordinates to force the Germans to broadcast those exact same encrypted coordinates.

-

For ACPA:

US Navy in WWII: The US Navy during WWII discovered that Japan was planning to attack a location known as "AF". They logically guessed "AF" refered to Midway Atoll knowing that other locations in Hawaii started with the letter A. In an effort to trap Japan, they chose to send a plaintext message from Midway Atoll stating that the atoll is suffering a severe shortage of water. By the time the US Navy intercepted Japan's confirmation message "AF is low on water", they confirmed that "AF" meant "Midway Atoll".

Cryptographic Building Blocks

Confidentiality: Encryption

There are different methods to encrypt a message. One type of encryption is called Substitution Cipher and the other is Permutation Cipher (ciphers can have both).

-

Substitution Cipher: It uses a substitution table ("key") to replace plaintext elements (bits, letters, or blocks) into ciphertext or vice versa. If the adversary does not have access to the subtitution table, they will not be able to decrypt it.

-

Permutation (or Transposition) Cipher: It rearranges or reorders the positions of the plaintext elements based on a key (fixed algorithm) to form the ciphertext. If the adversary does not know the specific transposition pattern or rule, they will not be able to decrypt it.

-

Product Cipher: A combination of both substitution and permutation.

Alongside encryption methods, cryptologists have also developed two popular encryption types, Stream Ciphers and Block Ciphers:

| Type | Description | Properties | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stream Ciphers | It is mainly a substitution cipher that encrypts data bit by bit (or byte by byte). They are faster and less complex to implement. | Employs Confusion only | Caesar cipher: it is a substitution cipher that commonly uses ROT13 (rotate 13) algorithm where half of the letters in the English alphabet are mapped to the other half. |

| Block Ciphers | Unlike stream ciphers, it processes fixed-sized blocks by reordering or rearranging bits within each block. It can incorporate both substitution and permutation. | Can employ both Confusion and Diffusion | - DES (Data Encryption Standard): Block sizes are 64 bits - AES (Advanced Encryption Standard): Block sizes are 128 bits |

Getting into the nitty-gritty details of both DES and AES deserves a separate article (will require familiarity with advanced math knowledge), but both use multiple rounds of transformations (substitutions and permutations) to strengthen security, though they do so in different ways.

For people who are still curious, I highly recommend checking out Neso Academy's videos on DES and AES. They are perfect to get an overview on how it works. For DES, I have linked a playlist starting with him teaching about the Feistel Structure (which forms the basis of DES). The latter link is a mere introduction to AES.

Demo with OpenSSL

OpenSSL is the swiss army of cryptography. You can encrypt, decrypt, hash, and so much more for anything IT security related.

- For this demo, we'll use RSA. We first generate a private 2048-bit RSA key (Base64 encoding). This will create an output file

private_key.pemthat includes a bunch of random characters.

Note: Your best friend is

openssl -help. You're free to type the examples on your own as you do -help your way through.

.pem (Privacy Enhanced Mail) is a text-based (not binary) file format that includes base64 data. The reason why it's showing in ASCII base64 is because genrsa subcommend is intended for portability to maintain intact in different OSes.

openssl genrsa -out private_key.pem 2048

- The next step is creating a public key based on the private key. So we use the

rsasubcommand to implement it.

openssl rsa -in private_key.pem -outform PEM -pubout -out public_key.pem

-outform means ("output in encoding format"). It can be PEM, DER (binary), or PVK (Microsoft proprietary encoding)

-pubout means output a public key.

- Now we have the public key and the private key. We will share

public_key.pemfor other people but keepprivate_key.pemout of sight. With these, we can start writing a message to a random file.

echo 'This is a secret message, for authorized parties only' > secret.txt

- Encrypt the message with our private key

openssl rsautl -encrypt -pubin -inkey public_key.pem -in secret.txt -out secret.enc

The rsautl subcommand signs, verifies, encrypts and decrypts RSA keys (note that it's deprecated since OpenSSL v3.0, but we're stick to using it for demonstration purposes).

pubin means the input file in question is an RSA public key.

The -inkey *val* requires an input key. The succeeding command argument is the public key filename (so, public_key.pem).

We will get a .enc file. This file is an encrypted form of secret.txt.

- Now that we're ready to decrypt it, we do:

openssl rsautl -decrypt -inkey private_key.pem -in secret.enc

This will give us secret.txt.

- Great! Now we want to apply authentication to

secret.txtby applying a hash digest like so:

openssl dgst -sha256 -sign private_key.pem -out secret.txt.sha256 secret.txt

-sign *val* requires a value. The succeeding command argument is the filename of a private key (so, private_key.pem).

- Alright, now we have the hash digest secret.txt.sha256 for secret.txt. We can now use the hash to verify the file.

openssl dgst -sha256 -verify public_key.pem -signature secret.txt.sha256 secret.txt

This will give us:

Verified OK

For more info on OpenSSL, I highly, highly recommend checking out this article by Paul Heinlein.

Hashing/Digital Signature

Hashing is a technique that turns plaintext into a unique string of alphanumerical characters allowing for quick access of data. Unlike encryption, it cannot be decrypted and is instead primarily used to ensure of data integrity as it discards a lot of information. So, even if someone tries to reverse the algorithm that ran the hashing, it will still be meaningless.

In order to determine if the hashing algorithm is good for production use, there are two requirements:

- One input must yield a unique output (called a "hash" or "digest") with a predefined size.

- No two different inputs must have the same output (this is known as preventing a "hash collision").

The hash SHA-256 (the most popular one) for "Hello world!" will give us this:

echo "Hello world!" | sha256sum

0ba904eae8773b70c75333db4de2f3ac45a8ad4ddba1b242f0b3cfc199391dd8 -

Even a slight change of lowercase w to uppercase W will result to a completely different string of letters:

echo "Hello World!" | sha256sum

03ba204e50d126e4674c005e04d82e84c21366780af1f43bd54a37816b6ab340 -

Common uses of hashing include:

- Hash Tables:

- It is a data structure that tracks a given key-value pair ("key" being the hash and "value" its corresponding actual value). There are sorted and unsorted ones depending on the implementation. Each key must be unique.

- In various programming languages, you can create your own object of a hash table or you can use predefined ones depending on your threading requirements and implementation.

- E.g.

dictin Python,Hashtable(thread-safe) andHashMap(non-thread-safe) in Java,std::unordered_mapin C++.

- Cryptographic Hash:

- Instead of storing sensitive data like passwords or unique username IDs on a database (a huge no), we can store their hashes instead to ensure integrity. This adds one layer of security in case of a data breach.

- In case of a data breach, combining salts with hashes (salt+hash from password) adds an extra layer of security. A salt can be any random string of letters added to the hash. This will waste hackers' more time and discourage them from fullying relying on plaintext/hash lists (rainbow tables) and brute force their way to crack account credentials.

- For those who are curious about rainbow tables, I highy reccomend watching this video by Best Mind Like. He goes into how to crack hashes using

rtgenandrcrackfor ethical purposes (to try out therainbowcrackpackage, download from here).

- Checksum:

- Verifies data's authenticity and prevents errors from happening while installing a file or transferring files from one network to another.

You might encounter similar things like "digital signature" and "MAC". Let's clear all that out of the way:

| Feature | Hash | Message Authentication Code (MAC) | Digital Signature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integrity: Validate that data has not been tampered with or corrupted. | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Authentication (Private Key): Validate the sender using a shared secret/private key. | No | Yes | Yes |

| Authentication (Public Key): Validate the sender using a public key. | No | No | Yes |

| Non-Repudiation: Prove that the sender has written and published a message. | No | No | Yes |

| Kind of Keys: | None | Symmetric | Asymmetric |

"Hash", "MAC" and "Digital Signature" all share the same purpose. Although they are all bits of authenticating info, each is to be used differently.

Note: MAC is actually a bit different from hash. Unlike a hash, MAC has its own suite of algorithms. When articles write "MAC" that talk about verification of data and checksum, they usually mean "HMAC" (hash-based MAC). I will only mention HMAC in this article as it is the most popular type of MAC since it is embedded in TLS (see NIST's link here for more info about MACs).

- Hash: The hash itself does not provide any security guarantees. A simple hash can only be used for data integrity and does not utilize any private/secret keys.

- MAC: The main type, "HMAC" performs a hash function of a data and combines it to a secret key (notice I did not say private key?). Take a look at the picture below (I'm going to call "Bob" the "Sender" and "Alice" the "Receiver"):

- Preparation: Bob and Alice both have the same Shared Secret Key.

- Encryption: Bob encrypts the message using AES with the secret key.

- MAC Generation: Bob takes that encrypted message + the secret key and runs them through the HMAC algorithm (e.g., HMAC-SHA256) to get a MAC tag.

- Transmission: Bob sends the Encrypted Message and the MAC Tag to Alice.

- Verification: Alice takes the received encrypted message + her copy of the secret key and generates her own MAC.

- Comparison: If her MAC matches the one Bob sent, she knows the message is authentic and hasn't been tampered with.

- Decryption: Only after the MAC matches does Alice use the secret key to decrypt the AES message.

- Digital Signature: This is also hash based but both endpoints use different keys instead. This requires asymmetric encryption where Bob will use the private key to create the signature while Alice will use the public key to verify. The message can never be forged because only Bob must have sent the message, no one else (true meaning of non-repudiation).

Demo with md5sum and shasum

Unlike openssl dgst, md5sum and shasum are both specialized GNU coreutil commands for hashing. The key differences are that openssl dgst is more general-purpose with faster wait-times, multiple options, and have different outputs.

Let's try hashing secret.txt with md5 by calling openssl dgst. There are two ways to do it, one is without using a redirecting operator > and one is with requiring the -r operator.

openssl dgst -md5 -out file.txt.md5 file.txt

Or

openssl dgst -md5 -r file.txt > file.txt.md5

The -r operator will turn openssl to behave like md5sum but it only reads in binary mode. Moreover, it has the advantage of overwriting the digest as well.

Output Without -r:

MD5(file.txt)= c7a8ef893898f9a6b380eb4ec1e87113

Output With -r:

c7a8ef893898f9a6b380eb4ec1e87113 *file.txt

Now let's use md5sum. Since md5sum by default outputs to stdin, we'll then type > to redirect stdout contents to a specified file (in this case, secret.txt.md5).

md5sum secret.txt > secret.txt.md5

Output of secret.txt.md5:

c7a8ef893898f9a6b380eb4ec1e87113 file.txt

It's up to you to choose md5sum or openssl dgst. If you use awk or sed a lot, you might prefer md5sum. Otherwise, you can give both a shot.

Ok, we'll move on with md5sum.

To verify if the hash is good for file.txt. We pass in the -c argument.

md5sum -c file.txt.md5

We should get:

file.txt; OK

If we do a little change on the original file file.txt, we'd get this:

file.txt: FAILED md5sum: WARNING: 1 computed checksum did NOT match

For shasum, it's the same idea (Note that shasum uses SHA-1 by default. If you want SHA-256, you'll need to type sha256sum or shasum -a 256). I'll leave that up to you as the syntax is identical.